Uganda: From Colonisation to Independence, Through the Bush War, and Now

The Pre-Colonial Period

The British could have gained their interest in Uganda thanks to explorers John Hanning Speke and James Grant, the first Europeans to step foot in Uganda in 1862, who were searching for the source of the Nile, which is located on the north of Lake Nalubaale (i.e. Lake Victoria). Speke and Grant’s “discovery” is noted to be one of the greatest moments in European African exploration and could be credited to other explorers entering the region, such as Anglo-America explorer Henry Morton Stanley, who quickly connected with Kabaka Mutesa I (1856 – 1884) of the Buganda Kingdom upon arrival. Stanley and Kabaka’s connection, and maybe friendship, led to the admission of Christian missionaries into Uganda, ultimately making it easier to establish Uganda as a British protectorate.

British colonial rule was consolidated in Uganda in 1890 thanks to a treaty with the Buganda kingdom. This was closely followed by the 1894 declaration of a British protectorate over Uganda, in which the areas of administration extended beyond the Buganda borders to include other kingdoms, such as the Kingdom of Toro in 1900, the Kingdom of Ankole in 1901, and the Kingdom of Bunyoro in 1933.

The Colonial Period

The famous Berlin Conference of 1884 – 1885, whereby the European powers partitioned Africa and like many African countries, this is how Uganda’s borders were determined. The borders were made with no regard for the ethnic composition and diversity of the area. This geopolitical decision has had and continues to have a lasting impact on Uganda’s history and identity. Uganda was created out of several historical kingdoms in the south: Buganda, Bunyoro, Toro, Ankole, and Busoga and the Nilotic, Nilo-Hamites, and Luo tribes in the north.

As one of the most powerful kingdoms was the Buganda kingdom, which had a centrality and organisation, the British focused on asserting control over Uganda through them. This was certified through the 1900 agreement between British and Buganda chiefs, which acknowledged British sovereignty and gave Baganda chiefs privileged status. The agreement allowed the British to institute a system of indirect governance, relying on the Buganda kingdom to conquer and administer other kingdoms within Uganda’s borders. This meant that the Baganda played a central role in colonial administration until independence, and their close association with colonial power gave them privileged positions in Ugandan society, reflected in the country’s name and the widespread use of Luganda in most parts of the country. However, this caused tensions within the country, as the Baganda received preferential treatment, while the Nilotic and Nilo-Hamites tribes of northern Uganda were considered more “backwards” by the British. It is due to this sentiment that the northern region was not developed during the colonial period and served mainly as a reservoir for cheap labour to be deployed in the south and soldiers for the British in order not to bolster the already disproportionate power of the Baganda.

Independence

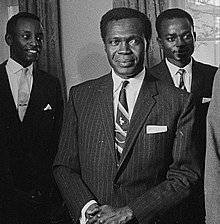

Uganda gained independence from the British on October 9, 1962, following the Uganda Constitutional Conference in 1961 at Lancaster House, which gave the Buganda Kingdom special status in the new republic of Uganda upon independence. The Independence Constitution granted full federal status to the Buganda kingdom and semi-federal status to several other southern kingdoms. In 1962, at the general elections before independence, Apollo Milton Obote of the Uganda People’s Congress (UPC) and the Kabaka Yekka (KY) struck an alliance known as UPC/KY Alliance, which provided the strength to form a coalition government with Obote as the Prime Minister and Kabaka Mutesa II (1939–53 and 1955–66) as President when Uganda became a republic in 1963.

Eventually, the coalition broke apart over disagreements with the Kabaka, one of them being about the Bunyoro territory, which the British had transferred to Buganda as a reward for their loyalty. In November 1964, Obote submitted the disagreement to a referendum, which led to the return of some of the disputed territory to the Bunyoro. However, the referendum only increased discontent with the Obote administration in Buganda. In 1964, Secretary-General Grace Ibingira, not believing in Obote's capability to be Prime Minister, initiated a way to gain control of the UPC, ultimately aiming to depose Obote from the party presidency. This was done by accusing Obote and Deputy Army Commander Idi Amin of being involved in a gold and ivory scandal. In response, in 1966, Obote arrested the main plotters, suspended the 1962 Constitution, and promoted Idi Amin to Army Chief of Staff. Obote even went as far as sending the army into the Kabaka’s palace and drove Kabaka Mutesa II into exile in London.

With the Kabaka gone, Obote proclaimed a new republican constitution, formally abolishing the kingdoms and becoming Uganda’s first President. Over the following years, Obote consolidated his powers by introducing a new constitution in 1967, abolishing the kingdoms of Buganda, Bunyoro, Toro, and Busoga and further strengthening executive powers. Then, in 1969, there was an assassination attempt on Obote, which led to the UPC banning all opposition groups and ineffectively creating a one-party State, causing further dissatisfaction with Obote’s government.

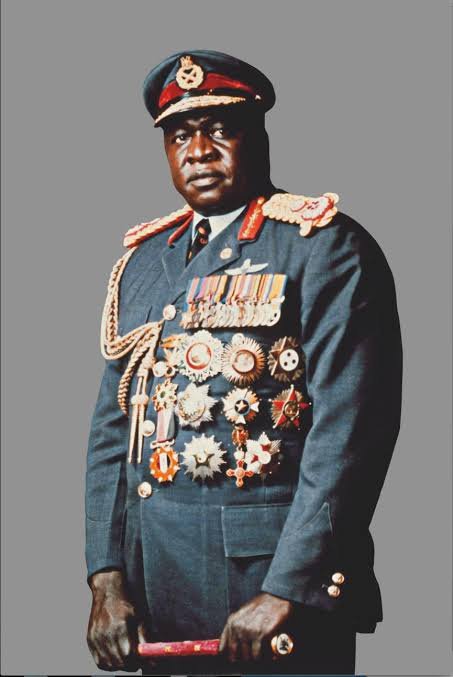

The Rise of Idi Amin

In October 1969, Obote introduced the Common Man’s Charter, a document that detailed the country’s Move to the Left, a policy direction towards socialism. Western capitalists, mainly the British, approached Idi Amin with the idea of toppling Obote. Obote was privy to Amin’s movements and decided to limit Amin’s power base within the army. This only convinced Amin that Obote was attempting to neutralise him, creating tension between the two. So, on January 25, 1971, when Obote was at a Commonwealth Summit meeting in Singapore, Amin took power, which was welcomed at first by many Ugandans, especially those living in Buganda who were dissatisfied with Obote’s increasingly oppressive government. They were even more pleased when Amin released many of those that Obote had detained and allowed Kabaka Mutesa II’s body to return from England for burial.

However, the bliss of Amin’s rule ended when certain aspects of his government came to light. Amin killed officers and enlisted men whom he saw as rivals for power. In 1972, in an attempt to increase national participation in the economy, Amin ordered the expulsion of Uganda’s citizens of Asian origin.

In 1979, those in exile in Tanzania tried to invade Uganda through the Kagera Salient in Tanzania, to which Amin pushed them back into Tanzania. In response, President Julius Nyerere of Tanzania ordered his troops, which were joined by various anti-Amin Ugandan militias under the Ugandan National Liberation Army (UNLA), to invade Uganda and drive Amin out, to which they succeeded.

The Bush War

After Amin was driven out, Yusuf Kironde Lule was president from April 13 to June 20, 1979. Then, there was Godfrey Lukongwa Binaisa from 1979 to 1980, followed by Paul Muwanga from May 12 to May 22, 1980. It was in December 1980 that Uganda got a stable president again following the general elections. During the elections, there were four parties: the Uganda People’s Congress (UPC), the Democratic Party (DP), the Uganda Patriotic Movement (UPM), and the Conservative Party (CP). The elections resulted in UPC winning, which was still headed by Obote, meaning he returned to Uganda again, often referred to as the “Obote 2” regime. However, his election was disputed by the DP.

These disputed elections led Yoweri Museveni, the leader of the UPM, to form the National Resistance Army (NRA) and wage guerrilla warfare. Museveni claimed to argue that his call to arms was a legitimate response to undemocratic practices. He also claimed that the struggle against Obote was more than a power struggle; it was a struggle to free Uganda from the political manipulation of nonrepresentative political parties and to create a more democratic and representative system of governance.

The war carried on for five years until May 1985, when UNLA troops led by Brigadier Basilio Okello and General Tito Lutwa Okello (who are unrelated) deposed Obote in a coup, leading him to flee to Zambia. Thus, the Okello government, led by Tito Lutwa Okello, seized power on a platform of national reconciliation, urging all political parties and insurgent groups to join the new government. An offer that the NRA refused because Museveni was dissatisfied with the number of seats the ruling Military Council offered. Then, between August and December 1985, the Okellos and NRA engaged in unsuccessful peace talks in Nairobi, meaning Museveni continued his guerrilla campaign against the Okello government.

On January 25, 1986, Museveni and the NRA defeated the Okello government and took Kampala, effectively establishing themselves as the government of Uganda, and it has stayed that way ever since. When Museveni was first in power, having liberated Uganda from its political instability, the economy prospered, foreign investment returned and increased, and many Asian Ugandans returned to open businesses.

In the end, the 1995 constitution of the Republic of Uganda established an executive, legislative, and judicial branch, and since 1996, presidential and parliamentary elections have been held every five years.

Quick Facts:

Uganda is also known as the Pearl of Africa, a term coined by Winston Churchill in his 1908 book My African Journey.

Speke named Lake Victoria after Queen Victoria of England, but to the natives, it was called Lake Nalubaale, meaning the home of the Balubaale gods.

Kabaka means ‘King’ in Luganda, the language of the Baganda ethnic group in Uganda.

Uganda has about 56 tribes.

During independence, the Ugandan army was predominately composed of northerners.

Kabaka Yekka translates to ‘King Only’.

Kabaka Mutesa II was first deposed in 1953 by the British and then in 1996 by Milton Obote when he was exiled to the United Kingdom and never came back to Uganda, dying in the United Kingdom in 1969.

Further Reading:

Politics and the Military in Uganda, 1890–1985 by Amii Omara-Otunnu

Uganda Since Independence: A Story of Unfulfilled Hopes by Phares Mukasa Mutibwa

Uganda: Tarnished Pearl of Africa by Thomas Ofcansky

We Are All Birds of Uganda by Hafsa Zayyan